There are only two writers who could have written the following exchange. One of them you may be able to guess:

I was once asked, ‘Why celebrate a birthday party for a child too young to remember it?’

I answered spontaneously, ‘Because the world is real.’”

Asking a serious question about an unexamined aspect of normal life, where the question implies that the common custom is foolish; answering in a way that is unambiguously affirmative of the common custom but with a statement that appears to be an irrelevant truism; and of course, the omitted sequel, an explanation of the truism by describing the consequence of the world being real, (in this instance) that even unnoticed and unremembered good deeds have absolute value. The obvious writer is G. K. Chesterton, and if you told me that Chesterton had written a book entitled The World is Real, which starts from children’s birthdays and becomes a long meditation on the Dominical precept to “enter thy room, and the door having been closed, pray to Thy Father in secret,” I would believe you.

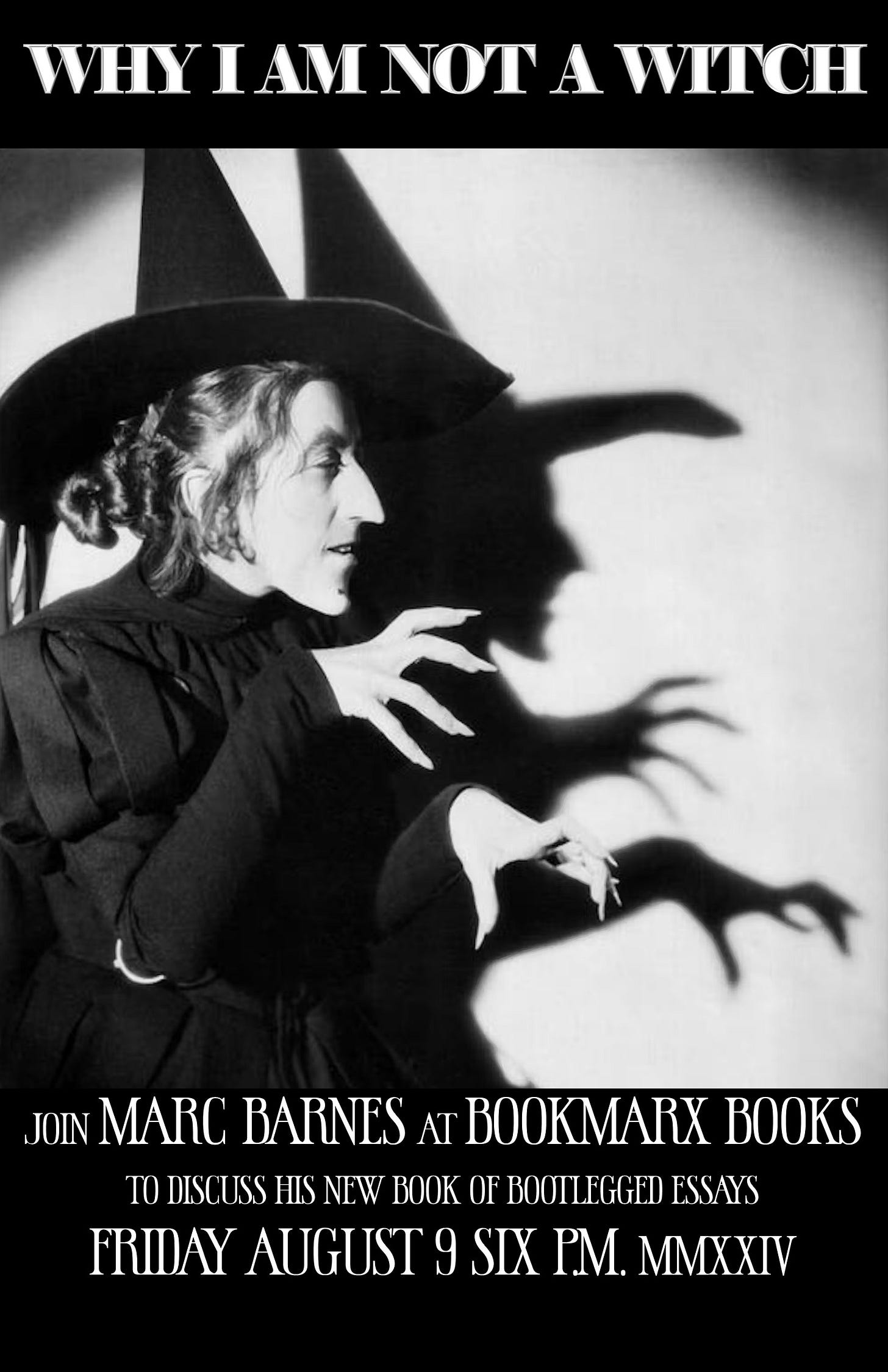

But the author of this exchange is not G. K. Chesterton. He’s a thoughtful young man and community leader living right now in Steubenville, Ohio, named Marc Barnes. Barnes has to his name a new collection of essays, entitled Why I Am Not a Witch. They are the most Chestertonian set of essays on Earth from anyone not dubbed G. K.

Another bit from our Chesterton redivivus:

A Christmas tree with its presents revealed lacks something, and if this seems mind-numbingly obvious, it is no less mysterious for the fact. Why should a gift be wrapped? We have all heard why stockings are a Christmas tradition, but isn’t it marvelous how quickly a child takes to it, prior to knowing a thing about St. Nicholas? “We put the presents in a sock! Yes! Of course.” To say we wrap our presents “for a surprise” must be correct. Even expected gifts are given as surprises. A father promises his son a bike for his birthday; his son anticipates the bike feverishly; still, the birthday comes, and what does the giver do with the gift? Hides it.

This is part of an essay which begins with the question “Why do gifts want to be wrapped?” It becomes an extended meditation on, of all things, biological sex – the aspect of a new life which is always a surprise, a thing hidden, and which must be revealed. The essay is remarkable, insightful, ingenious, odd – Chestertonian, in a word.

It is a promising fact that such a young writer should be stalking the streets of Steubenville. Much of his personal life outside the page is promising too: Barnes has started a grocery in Steubenville, in a downtown where gas stations and dollar stores are the most accessible sources of food. He is the front man of an organization which has organized a wildly successful monthly street fair, Steubenville’s First Fridays. He edits a new magazine, New Polity, where these essays first appeared. He is married with children. He has run for town council (and lost). In other words, he has shown himself completely willing to get his hands dirty and take up the hard work of the world, the sort of work that shows only the meagerest prospect of earning any worldly reward.

The essays also show some Chestertonian vices. They are prolix. There are paragraphs one feels might dissolve at the slightest touch, so overinflated are they. More typically one senses the author is simply in no hurry. Digressions appear to be mandatory. Most importantly, everything is just a bit too vague: we hear of “children” but never of Marc’s children; we hear of public spaces but never of a particular street or square in Steubenville. We hear that witches are hip but never of one particularly sensational witch. Barnes feels like a young writer who believes that the abstract will be universal, when it is the uniquely real which in fact has the broadest relevance.

This is why I am so happy the book has been published. They allow the public to see Barnes and gain a sense of where he is, which might give him the interlocutors who will cause him to burrow into reality a bit more. The book, amazingly, is only Barnes’ work in that he wrote the essays: it is a pirated edition which he found on Amazon selling under his own name. I purchased copies with his permission for my bookstore, and we are now selling them. Barnes theorizes that the publisher uses bots to identify online content by unpublished authors, pirates an edition, and sells until Amazon forces them to take the listing down. With print-on-demand technology there is almost no investment involved.

The result is that we have a little book of essays to enjoy. The title essay contains marvelous insight about witches, namely that they are cool today only insofar as they are historically oppressed; like Christian martyrs they are esteemed only if they have had their blood shed in the arena of life. In older days they were valued specifically because their magic would avert such a fate. But as for why Barnes has decided not to join these quasi-Christian witches, you’ll have to read the book yourself.